Event : A Century of Sounds: Live

Friday 27 February 2026, 18.30 - 21.00 A Century of Sounds: Live at Pitt Rivers Museum click here to find out more.

Experience reimagined global sound recordings from the Museum's collections through live performance, artist conversations and interactive activities. A unique after-hours event in collaboration with Cities and Memory and Oxford Contemporary Music.

A Century of Sounds: Live is a unique live event, bringing together the Pitt Rivers Museum's extraordinary sound collections with 100 artists from around the world to create a new way of experiencing these incredible, diverse recordings. This live event is the launch of the project collaboration A Century of Sounds between Cities And Memory and the Pitt Rivers Museum, where 100 artists were invited to engage with one of 100 sounds from the ethnographic sound archive of the museum and creatively reimagine it. Many of these sounds from the museum archive have never been made public before.

Listen to my creative reinterpretation of sound 74 of the 100, accession number 2012.70.50, Rock Gongs from Birnin Kudu, which will be embedded here and available to listen to on Pitt Rivers Museum website via Cities and Memory onwards from 27th of February 2026 !!

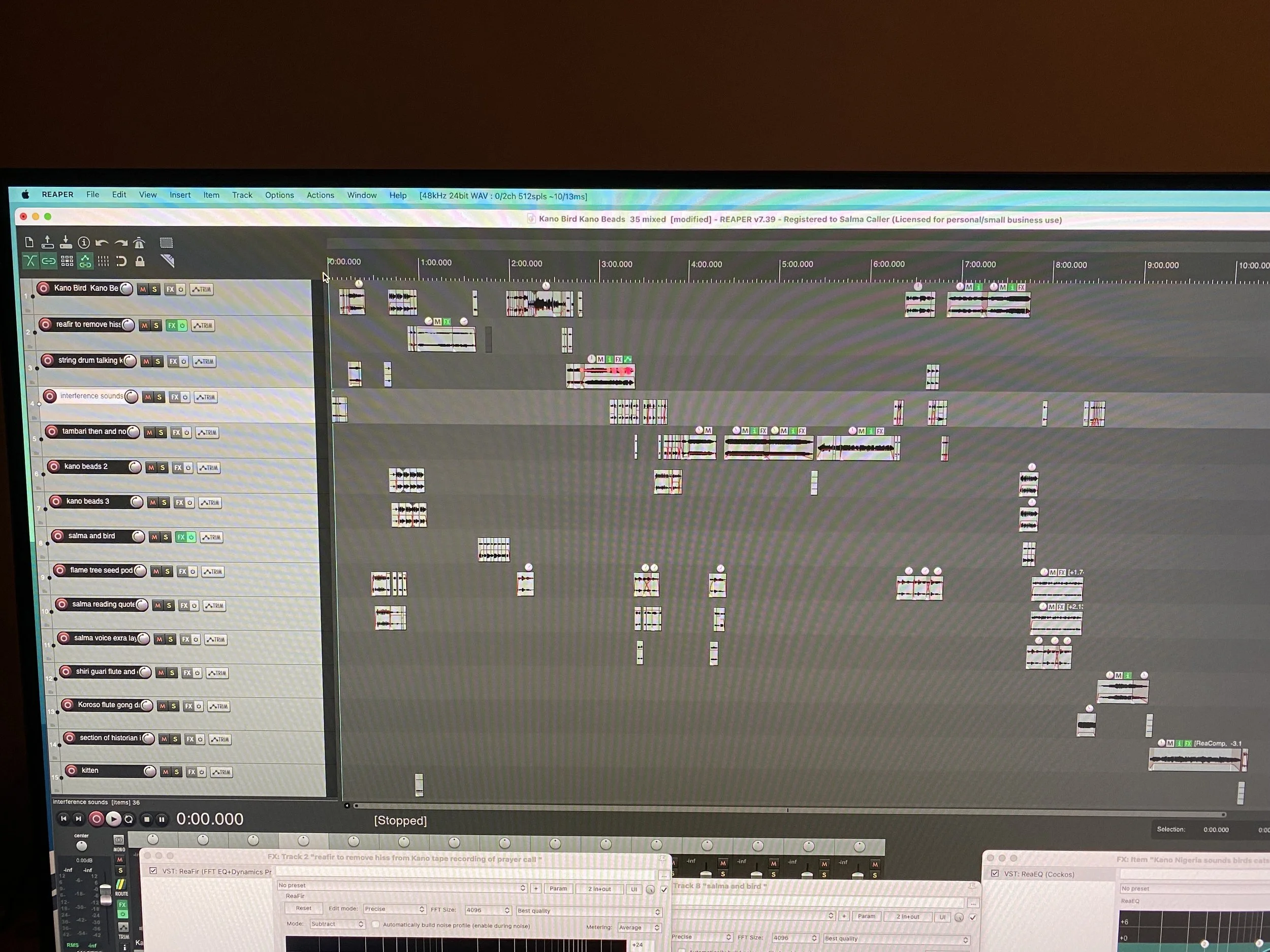

Kano Bird / Kano Beads / Kano Seeds

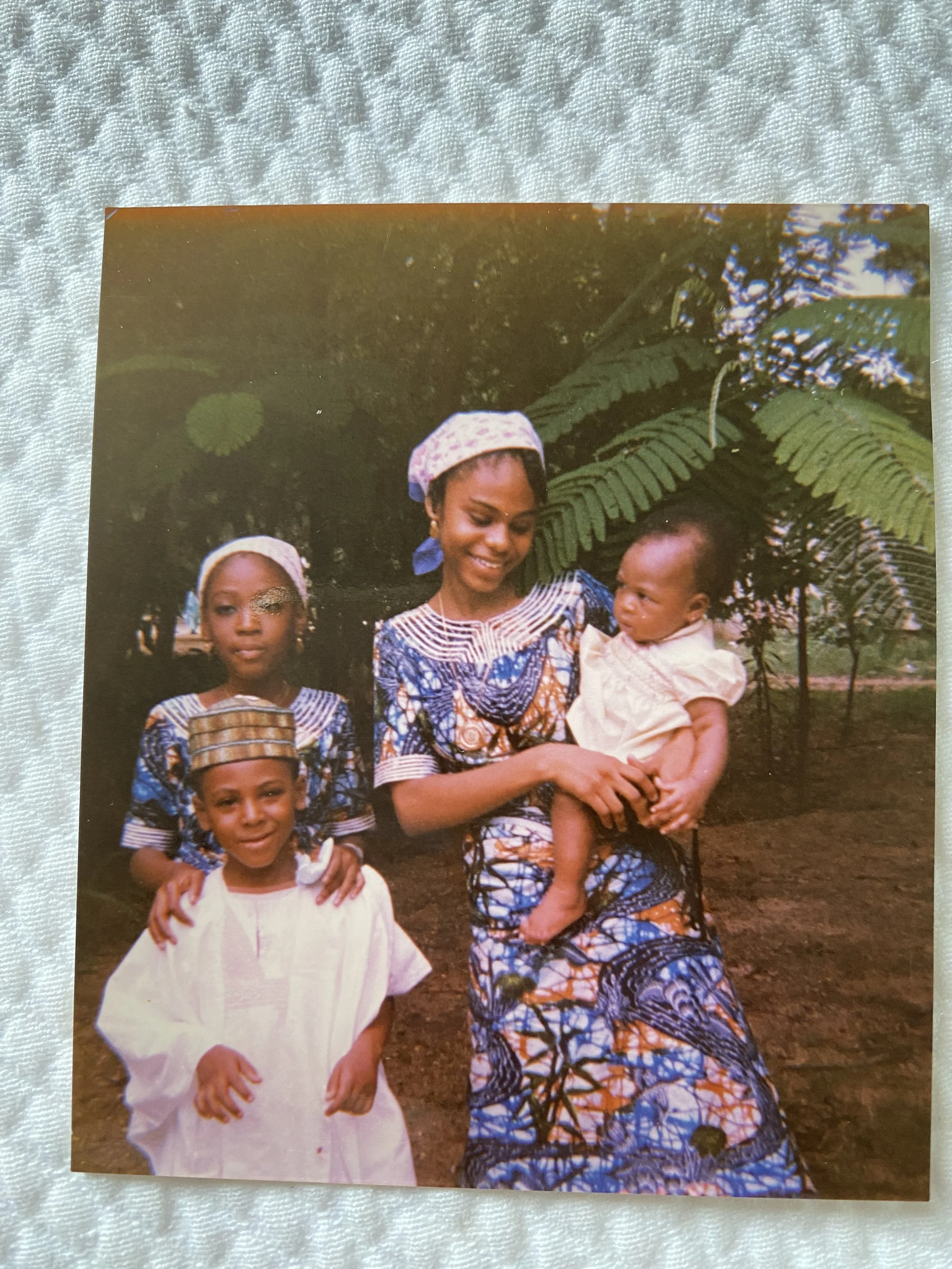

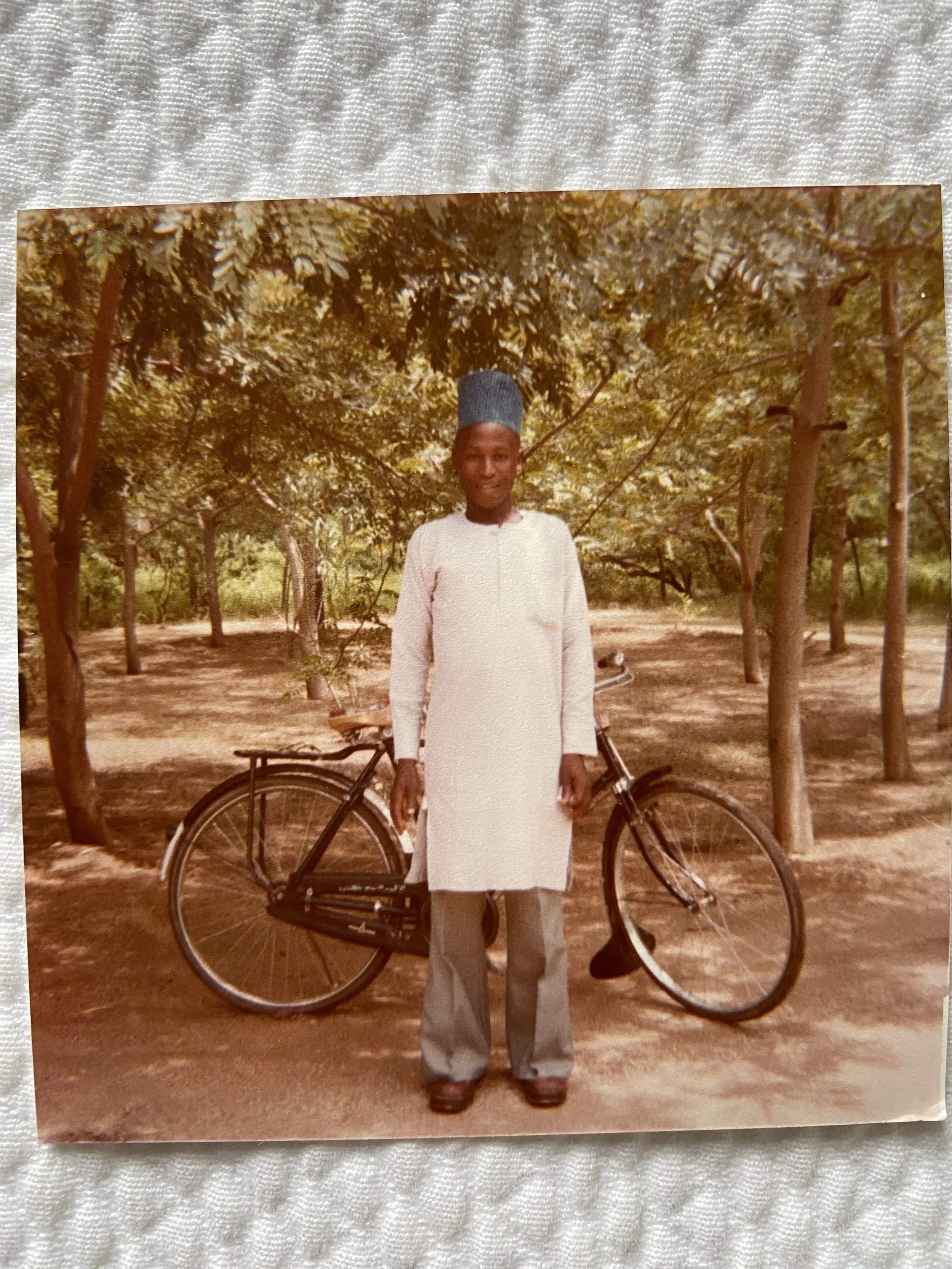

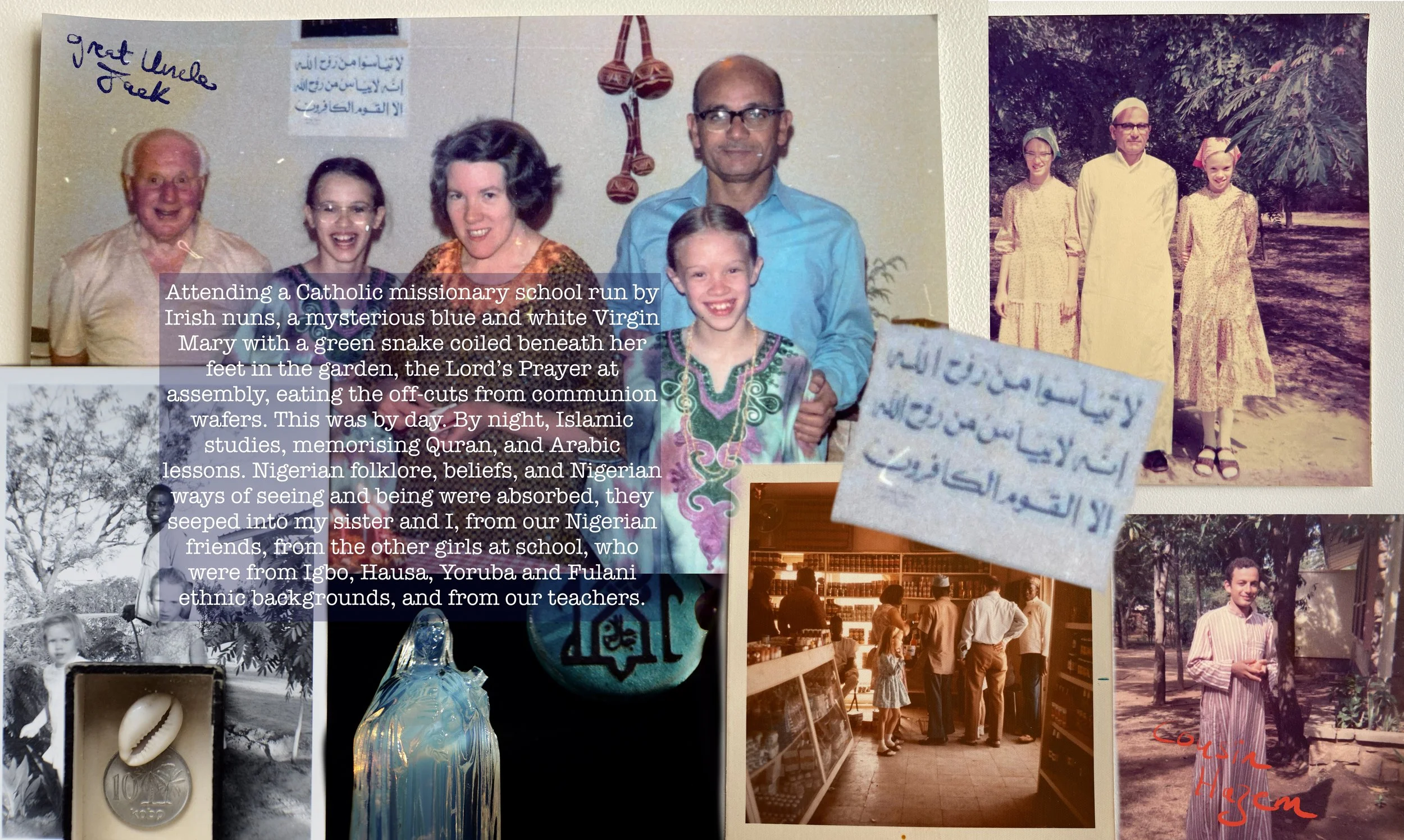

I grew up in Kano city, Northern Nigeria, from the 1970s to the early 1980s. My Egyptian father and English mother met in Oxford, and they moved to Kano for my father’s job, teaching Islamic studies, philosophy and Arabic at Bayero University.

As a sound artist, I work with sound fragments, sonic shadows and ghosts, interferences, pieces from forgotten archives, memory and identity, cross cultural collisions and entanglements, trauma, and the intersection of the personal and the political.

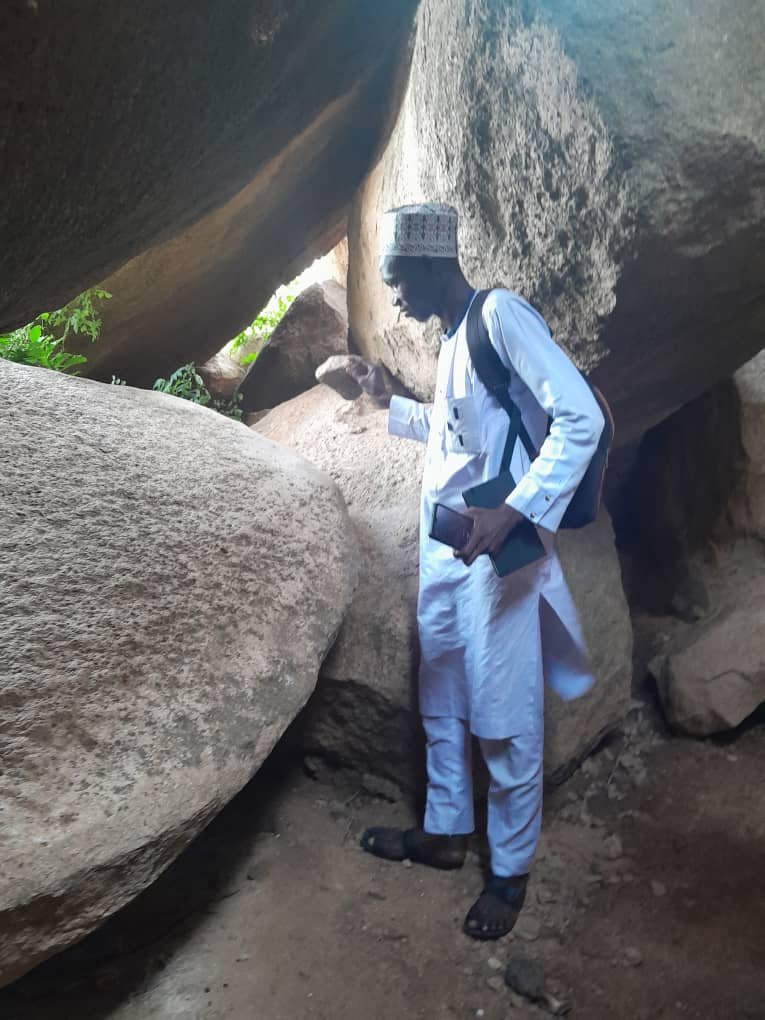

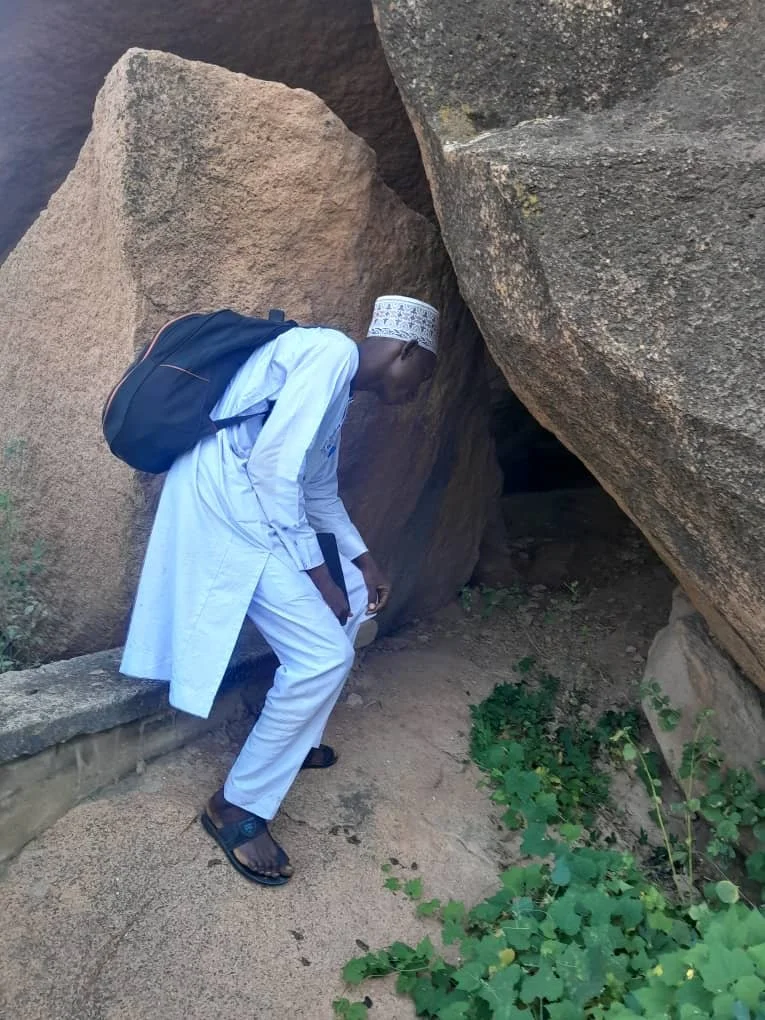

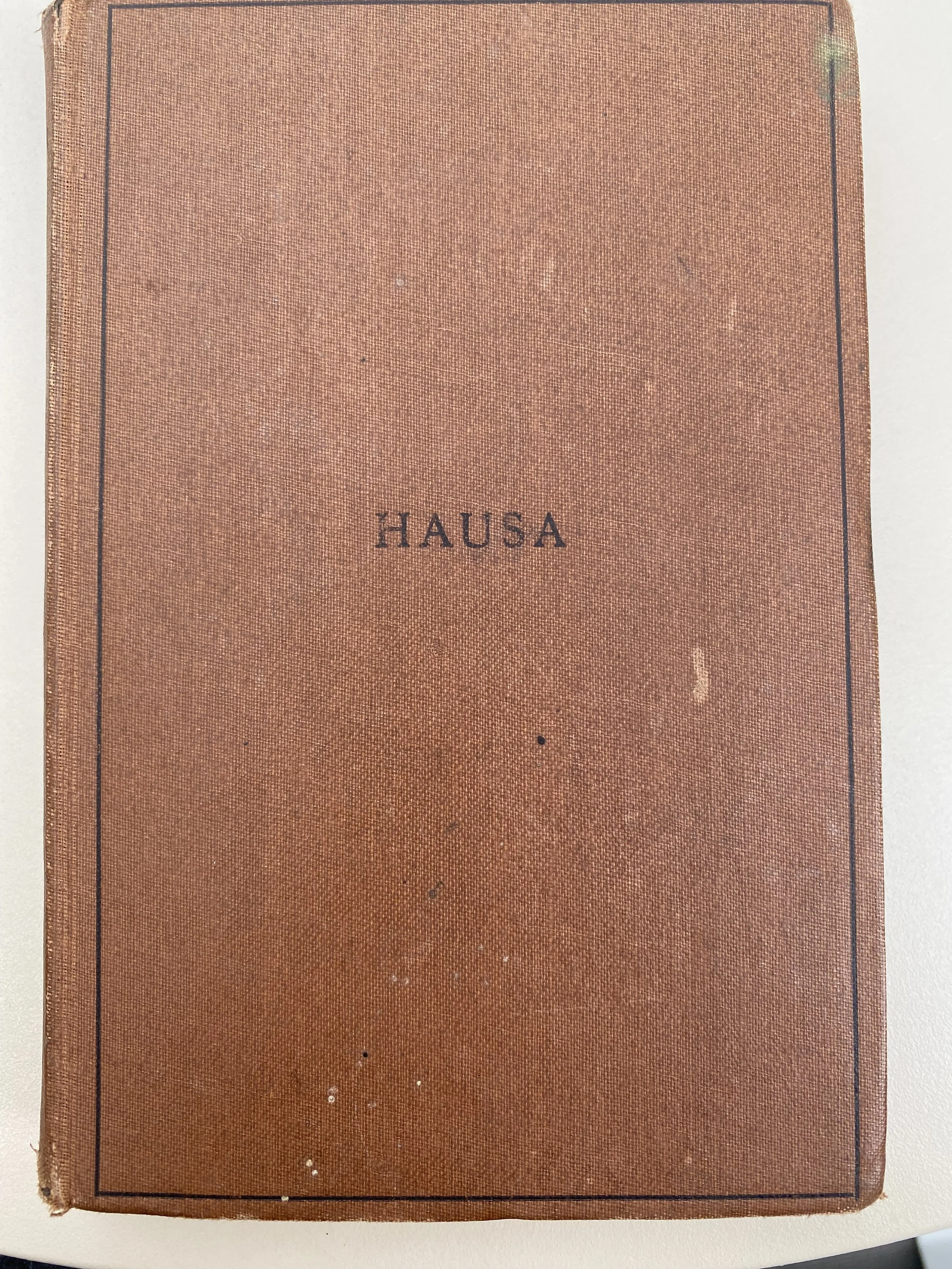

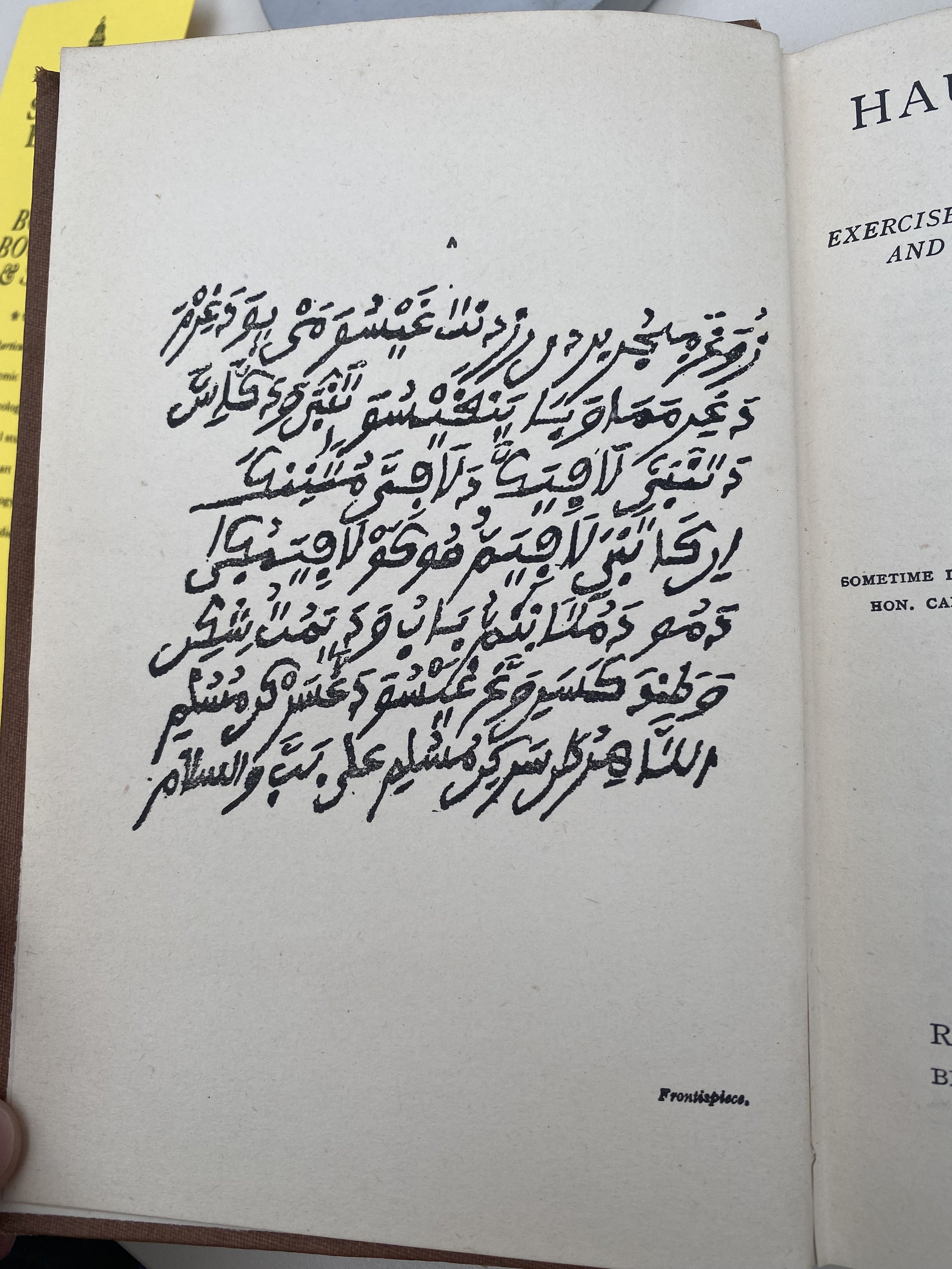

This sonic work is an attempt to communicate my profound childhood relationship with Kano, as well as to hint at the complex layers of Northern Nigeria. I have taken multiple fragments from a 5 inch reel tape recording held in the Pitt Rivers museum sound archive, accession number 2012.70.50. It was recorded by Bernard Evelyn Buller Fagg, between June and September 1955. He was working for the British Colonial administration in Jos, Nigeria. He was an archaeologist who was interested in rock gongs, and he came across several ancient caves, with rock gongs, and important cave paintings, in the area of Birnin Kudu, an old city with ancient history, in Northern Nigeria, that was once part of Kano state, that had strong trade ties with Kano old city.

Bernard Fagg seems like a nice fellow, and I have grown accustomed to his voice. His little sniff now and then. But he was also part of the British colonial power structure, and wanted material for the advancement of his research on rock gongs. He seemed to be having a great time with the local people, musicians and drummers he asked to volunteer to help him explore the sounds of the rock gongs. The drummers attempted to see if they could get the rock gongs to match their traditional rhythms. The various sections included sounds of the ‘string drum’ or Kalangu drum, a Hausa talking drum, the rhythm of the Tambari, used to greet chiefs and emirs. And many other local songs, and numerous types of drumming. I picked the ones that I loved most. Where possible I have tried to pair the rhythm on rock gongs with the rhythm on the drum itself. And I interwove the glitches and buzzing sounds from Fagg’s 1955 recording, as sonic interference - colonial interference, or my own presence, or maybe the sound of an old radio tuning into to the past.

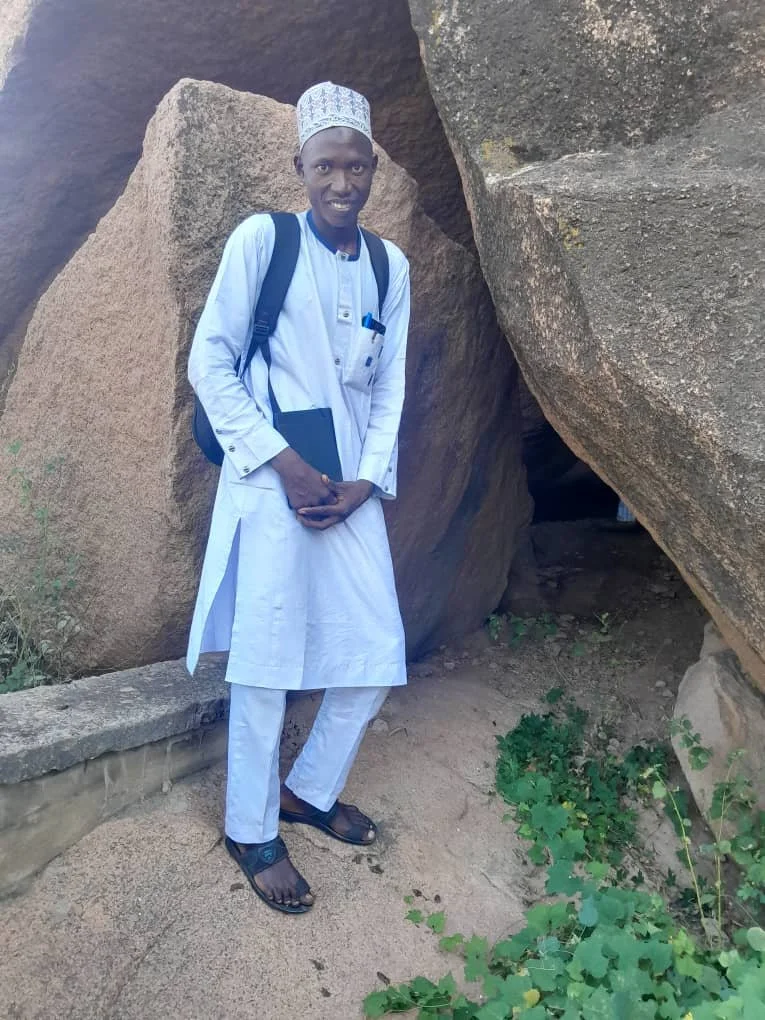

My best friend Halima, who I still talk to regularly, who was my neighbour in Kano, on the university campus, and we went to school together at the Christian missionary school, kindly asked her cousin Umar Shamsi Muhammad, a university student studying a Batchelor of Arts degree in Hausa Language, to help me with this audio project. Umar Shamsi went about Birnin Kudu, capturing sounds of students and curators beating the rock gongs in the main caves, of Mesa and Habude, and you can hear snippets in this piece. He also interviewed a historian of Birnin Kudu caves, Umar Farouk Abubakar. You can hear two fragments of this interview, as well as a Hausa / Fulani flute player and drummer, playing the Koroso dance in the caves. I wanted the sounds of the Hausa language, and contemporary Northern Nigeria to be part of this work.

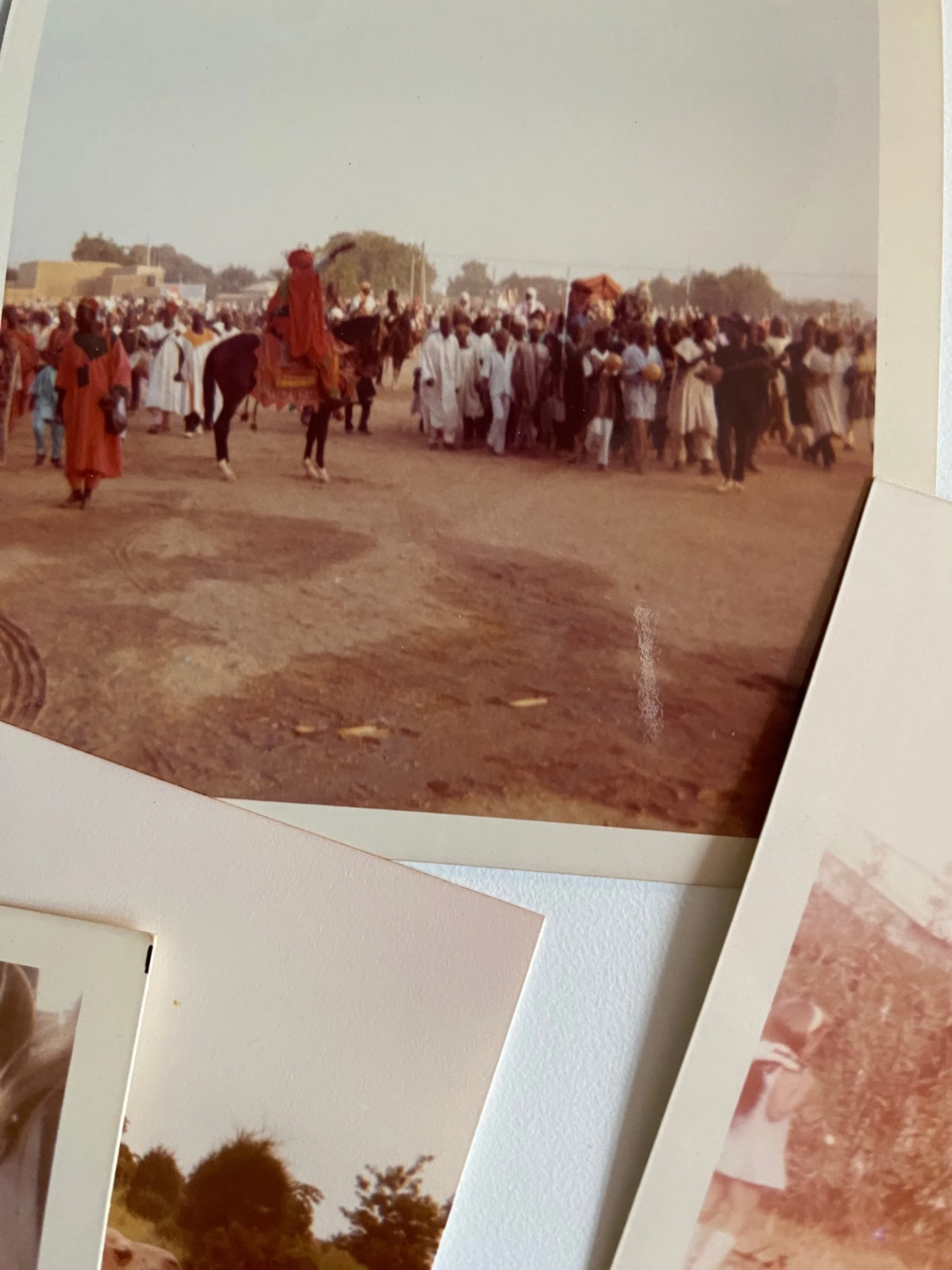

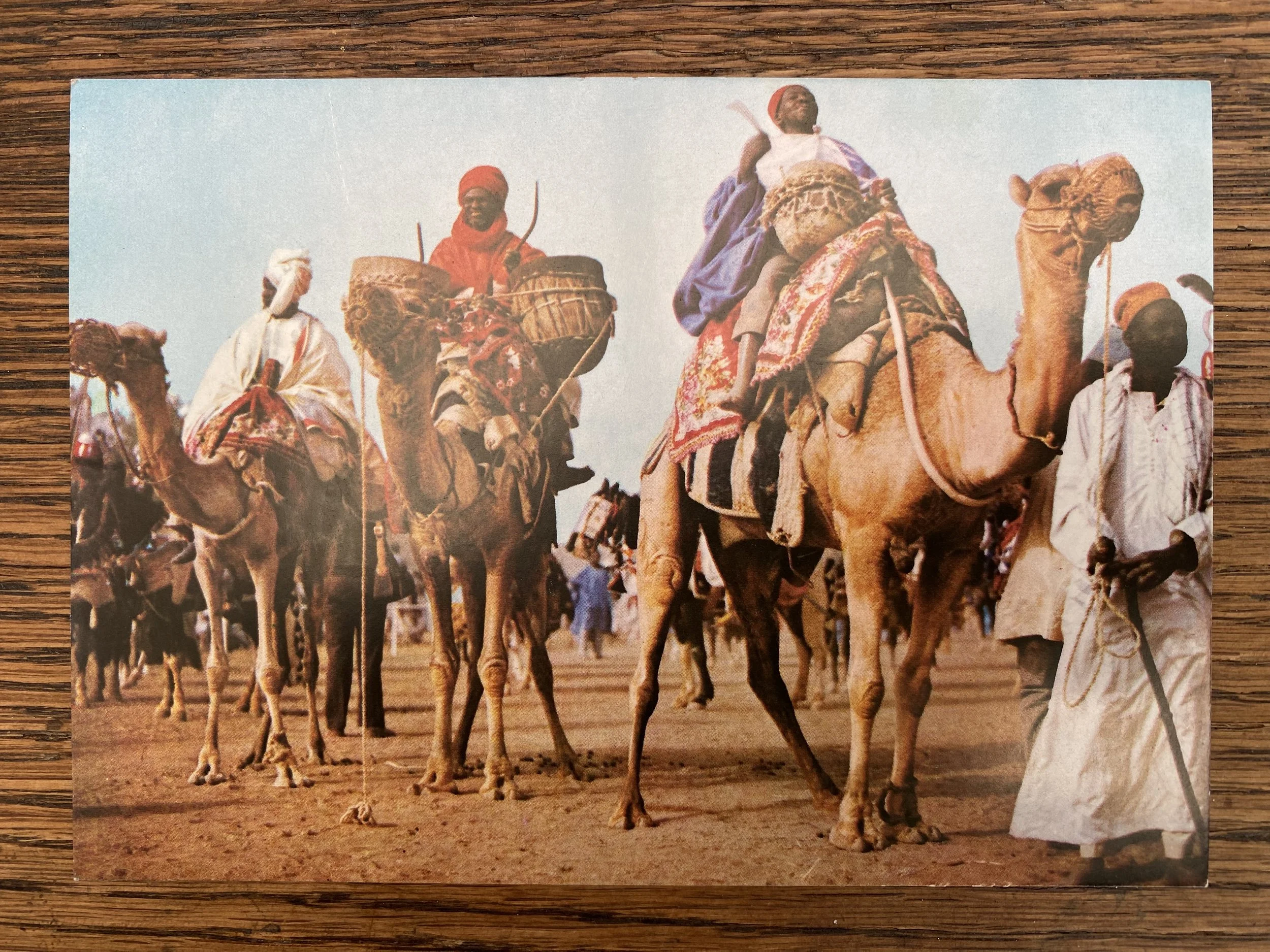

In the centre of this piece are the sounds of the actual Tambari drum, and the fascinating exhilarating sound of the double reed wind instrument called the Algaita, played recently in Kano, at the Durbar, for the greeting of the Emir of Kano, sent to me by Umar Shamsi. The deep sound of the Tambari beats inside your body like another heartbeat. This sound transported me back into the deep past. Kano was an important medieval city on the trans-Saharan trade route, and is located in the savanna, south of the Sahel. It was one of the seven Hausa kingdoms, and the Hausa and Fulani people are the majority. Centuries before British colonisation, it was a cosmopolitan trade city. Islam came to Kano and Northern Nigeria in the 11th century via traders, and people mixed Islamic and pre- Islamic traditions and practices. It wasn’t until 1809, under the Sokoto Caliphate, and after the Fulani war against the Hausa kingdoms, that the peoples were unified under an Islamic government.

Kano beads, which you can hear in this piece, are glass beads that were made in Palestine, from Dead Sea salt, and sand, and coloured with iron or copper oxides, made in the glassmaking city of Al Khalil (current day Hebron), supplying glass beads that were traded in Egypt, Sudan, Ethiopia and finally arrived in Kano city. In the 1930s the glass beads were no longer an important trade currency, and various tribes in Northern Nigeria began filing them flat on two sides so that the beads would sit neatly on a cord, to create necklaces that were associated with status. Hence they became known as Kano beads. Mine are dark green. These trade beads also have a dark history, as they were also used in the trade of human beings, across the centuries, along the trans Saharan route, but also particularly during the 1800s under the influence of European slave trading.

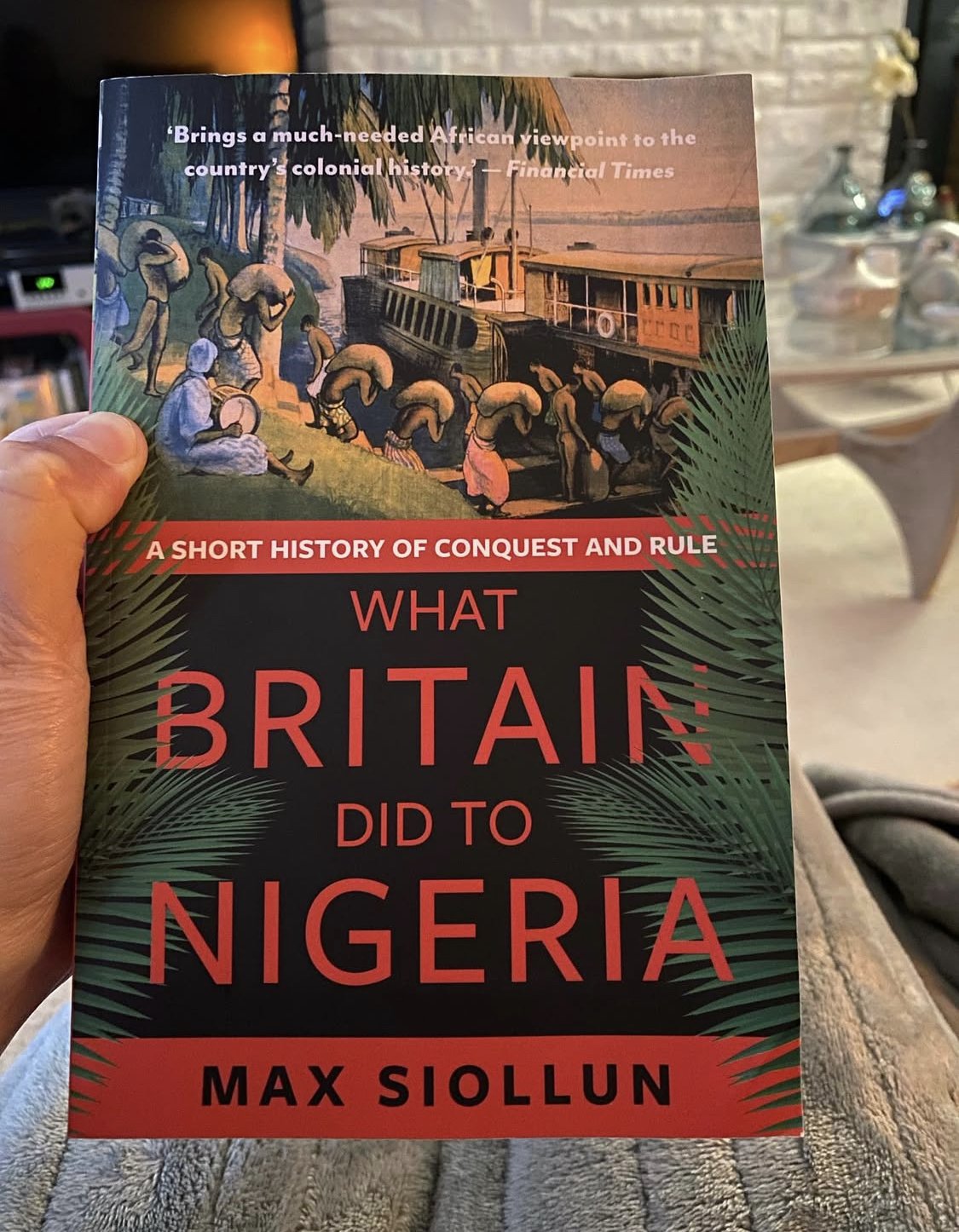

The British colonial project finally took control of the area that became called the Protectorate of Northern Nigeria, after many years of illegal trade and coercion, battles and killing, into the early 1900s. You can understand all about how Nigeria was created, and taken by the British, by reading the excellent book by Max Siollun, called What Britain Did To Nigeria, from which I have taken several quotes to read in this audio piece. Including a quote from a British solider who was part of the battle for the Sokoto Caliphate in March 1903, who describes the battle as ‘some slaughter, much fun’. A British officer explained ‘we chase and kill until the area is clear of living men - and we tire of blood and bullets’. I have included some of these disturbing quotes as one of the many layers in the strata of what makes up Northern Nigeria, because I think it is very important to understand the colonial British presence in this audio. But these should not distract from the beauty and complexity of the music and drumming.

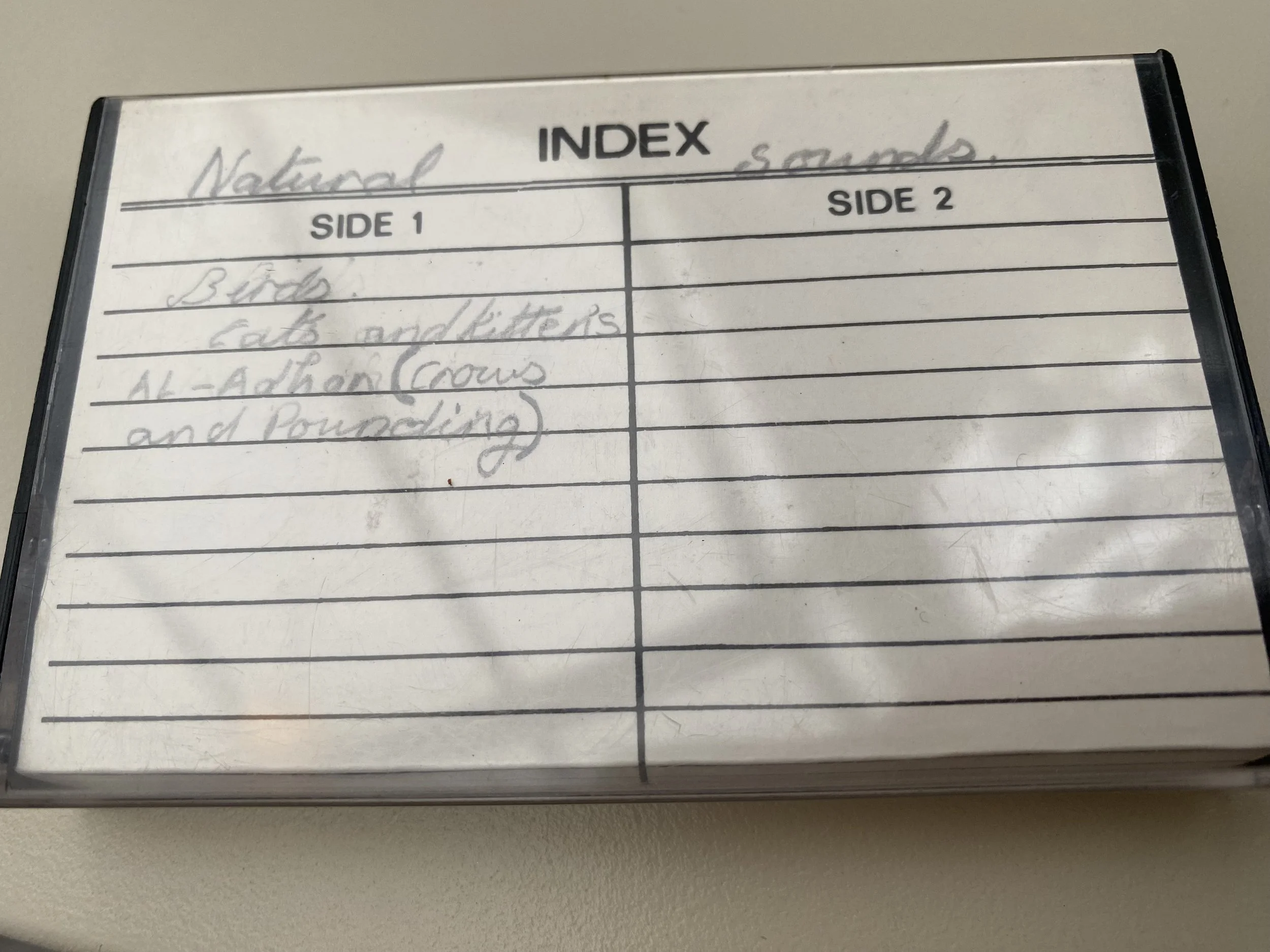

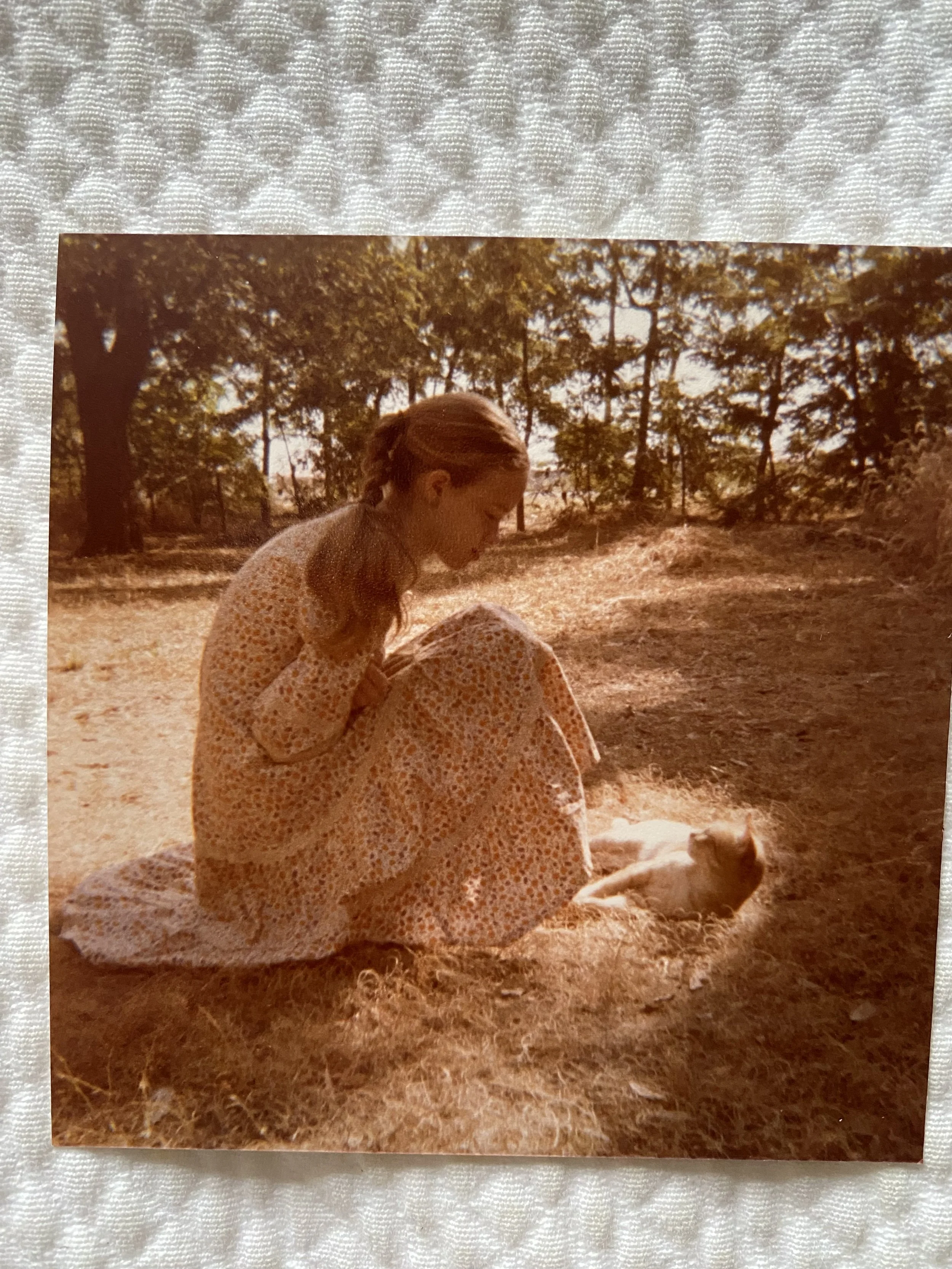

I created this piece as a kind of tapestry of interwoven time, of different eras, that, like tectonic plates, knock into each other, creating dissonance and vibrations, and blending in my personal memories of Kano. You can hear the sounds of my actual child self in the 1970s, that I recorded 47 years ago, using our cassette player, to capture a bird call, and myself mimicking that bird, called Ragon Maza in the Hausa language. You can also hear the sounds of my flame tree seed pod, from our garden in Kano, that has travelled the world with me in my suitcase, and now sits by my desk at home. The flora and fauna of Kano are speaking too. And you can hear one of our kittens.

And in the early part of this composition you can hear another section from my old cassette tape, which I found in 2020, when clearing my parents house, after the passing of my mother during Covid lockdown. Beyond the hiss, which seems like a sonic version of the mists of time, which was hard to remove, you can hear the sounds at dusk, one evening of my childhood, the distant prayer call from Kano mosque, with it’s intense green dome, and the sounds of evening crickets are very close by. Sadly, the sounds of pounding of yam can no longer be heard clearly enough across the years.